Our theme for this week’s Remote Humanities newsletter centers around discussing uncomfortable or controversial topics in the classroom, and creating inclusive spaces for different perspectives and types of participation. In addition to Ryan Solomon’s upcoming “Balancing Discomfort and Uncertainty in Learning: Dialogue as Pedagogical Strategy” workshop, we reached out to Hilary Strang, director of MAPH and senior lecturer, to ask about her approach to class discussions involving difficult subjects.

Our theme for this week’s Remote Humanities newsletter centers around discussing uncomfortable or controversial topics in the classroom, and creating inclusive spaces for different perspectives and types of participation. In addition to Ryan Solomon’s upcoming “Balancing Discomfort and Uncertainty in Learning: Dialogue as Pedagogical Strategy” workshop, we reached out to Hilary Strang, director of MAPH and senior lecturer, to ask about her approach to class discussions involving difficult subjects.

Although Hilary acknowledges that everything is different in the remote classroom, the basic underpinnings of her class discussions remain. She says that when she is hosting a discussion about difficult topics – meaning that the subject matter is sensitive or upsetting, or simply that it is complicated – her main goal is to monitor how students are responding. This is harder to do on Zoom, because “affect and atmosphere” can be lost or lessened in virtual conversations. “We don’t produce the same affective connections in the remote space,” Hilary says. But the essential questions that she keeps in mind during such discussions are the same: Who is gathered here? Why are they gathered here? Why are these discussions difficult?

When Hilary is asked about teaching, she often circles back to ideas about feelings and community, because she believes them to be omnipresent in academic and intellectual work:

“I’m a rigorous teacher! I ask people to read things that are difficult, and to think intensely. But I don’t see intellectual work as in any way at odds with trying to make classrooms into spaces that are caring and collective, or with taking seriously that people are different from each other and will be bringing different things into that space. If you let people connect with each other and you make it explicit that that’s what they’re doing, that’s just bringing to light what’s already there. None of us work or think by ourselves. It also helps us think about how the work we do here connects to the possibilities we want to see in the world. Thinking that the classroom can be a collective space helps you think about the kind of collectives you like to see, and how they’re prevented from existing in the world. Teaching and conversation and discussion is a human endeavor among human beings, and it only happens well when that’s something everyone is able to keep in mind.”

Although making space for difficult discussions in the classroom involves creating space for a collective experience, it also involves acknowledging the individual experience. Hilary knows that she has students with full-time jobs, or who are caregivers at home, or who might have a non-standard approach to learning. She also knows that she’ll sometimes have students who are just tired or zoned out on certain days, especially this year. She doesn’t see this as a barrier to a classroom discussion, but simply part of the equation. It is important to her that everyone in her courses is “able to be their human self and not feel that that is somehow excluded from the classroom.” This is expressed beautifully in her syllabus statement for her spring class, Ectogenes and others: science fiction, feminism, reproduction:

“Your main occupation this quarter is to find the best ways you can to care for yourself and others. What is the place of intellectual work in that? That’s for you to figure out, and your answer may change day by day or week by week. This class is structured around substantial discussion and reading, but it can also be flexible. Your well-being, whatever constitutes that for you, matters more than this or any class. If you are having any trouble with the class or otherwise, let me know. You don’t need to confide in me, but I will do what I can to help.”

Hilary tries to keep her syllabi minimal – “the class isn’t the syllabus; the class is something that we make together” – but she likes them to represent something. She knows that communication is harder during remote teaching, and that it is important to both put some things in writing and then continue to reiterate them verbally over the course of the quarter. Hilary believes that the most important thing that students can do right now is to “care for themselves and their communities.” In her courses this past year, a number of students demonstrated appreciation that she had continued to remind them of such things, and she realized that she herself benefited from those reminders.

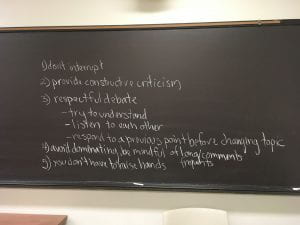

In addition to her syllabus statement, Hilary includes guidelines for “minimal and maximal participation” in her course. She does this in an effort to be explicit with students about what participation is and what it means, knowing that it is available differently for different people at different moments, especially now with the shortened quarter. Not every student will achieve a perfect standard of participation each time that the class meets. When asked how she grades her students across such a flexible range of participation, she says, “I care little to nothing about grades as an instructor, and I would prefer if our classes were ungraded. I don’t think they say a whole lot, and they can be actively harmful to learning. They demand a kind of measurement that can’t capture the amazing and interesting things that students do.” Instead, she tries to focus on how each student demonstrates their engagement with the materials, regardless of what that looks like for them. “People show up in ways that are great; they show up at the level that they’re at.” And especially at our current moment, “everyone should be being treated with maximal generosity.”

Hilary Strang is the director of MAPH and a senior lecturer in the Humanities, with affiliations in English and CSGS. She teaches classes on critical theory, science fiction, feminism and utopia. Hilary also teaches for the Odyssey Project, a Chicago-based adult education program accredited by UIC.